Shadows In

Dawnland

Wabanaki Tribes and the State of Maine set out to hear the truth about a painful past

Wabanaki Tribes and the State of Maine set out to hear the truth about a painful past

Dawn on the border of northeastern Maine.

Six-year-old Aubrey Sockabasin is in the backseat of a car. His brother is beside him. The driver is pulling away from their home on Indian Township in Princeton, Maine.

Aubrey turns in his seat to look back through the rear window to the front porch, where his father and stepmother stand, watching as they drive away. Panicked, a single question sears through his mind: why?

Though Aubrey Sockabasin was removed from his home and first placed into foster care almost 50 years ago, he says the memory of being taken away from the Passamquoddy reservation—self-governed tribal land—haunts him daily.

“I replay that moment over and over in my head,” he says. “To this day, I still don’t know why they took me away.”

For the Native tribes of Maine, Aubrey’s story is all-too familiar. The Wabanaki nations—which encompass the tribes of the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Mic’mac (or Mi’kmaq), and Maliseet—have watched as child after child has been removed from Native families by the state of Maine to be raised in non-Native homes. For generations, Native children were taken without warning, and even sometimes without the consent of their own families, further splintering the next generation of indigenous groups already fighting for the survival of their culture.

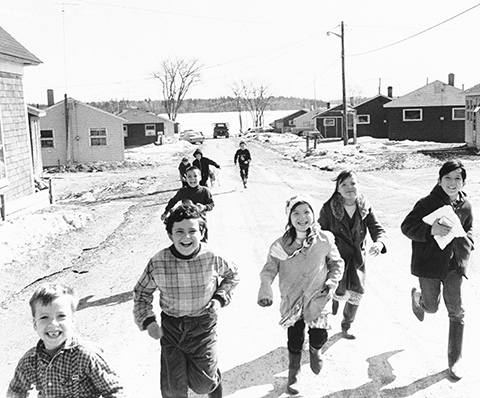

Passamaquoddy children at Peter Dana Point, Maine, April, 1969. (AP Photo)

Now, for the first time, these stories are being told publicly. Sockabasin is just one of the hundreds of Wabanaki—and non-Wabanaki—in Maine who are testifying before a special commission determined to bring out these histories from the shadows. The Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) began its work in 2012 and is now holding interviews and group sessions across the state in order to hear from all those affected by the practices of the state’s child welfare system. Its final report, detailing its findings and recommendations, is expected next year.

The TRC’s operations might seem smaller in comparison to other country-level truth commissions that have been set up in places such as South Africa and Peru to establish the truth about conflict or systemic repression. The number of testimonies collected by those commissions have numbered in the thousands. So far, Maine Wabanaki TRC staff say it has collected 130 statements.

But the story of the formation of the Maine Wabanaki TRC is a story of transformation in its own right. In the long, blood-soaked history of colonization and westward expansion in North America, the official silence over the extermination and cultural assimilation of America’s Native peoples is deafening. Never has there been a country-wide effort to fully address the legacy of colonization and the near obliteration of Native peoples from the Atlantic to the Pacific. And this devastating legacy lingers on: collective trauma has continued to be passed down through generations, compounded by the loss of language, traditions, and other forms of cultural heritage.

In the long, blood-soaked history of colonization and westward expansion in North America, the official silence over the extermination and cultural assimilation of America’s Native peoples is deafening.

Against this backdrop, what is transpiring in Maine is an historic, if not an extraordinary, moment in the history of the United States and indigenous peoples. How exactly, did it come to be, that—with the weight of centuries of war, land disputes, racism and economic tensions—the government and inhabitants of the people in the eastern-most corner of the United States came to undertake such an initiative?

The answer is a story that takes place in several sovereign nations, cities, towns, and reservations. It’s a story about children and childhood, of memory, loss, and hope. It involves social workers and professors, students and elders, activists and politicians. It’s a story of unlikely bi-partisan political agreements, unprecedented cooperation between Native and non-Native Mainers, all led by the unwavering determination of a group of Wabanaki women who want to make one thing absolutely clear: the truth, healing, and change we need has only just begun.

Peter Dana Point, Indian Landing, Maine (Jenn Vargas/Flickr)

After he and his brother were taken from their home from the custody of his father and step-mother by an agent of the state of Maine, it would be years until Sockabasin would see his parents—both full-blooded Wabanaki— again and decades before he returned to the Passamaquoddy reservation he once called home. Sockabasin and his brother were placed with a non-native family in Dennysville, Maine, about 30 miles south of Indian Township. He soon came to realize that the world he knew—family, culture, language—was about to be ripped away from him and put in its place would be abuse, isolation, and resentment.

“If we did something wrong, we’d have to stand in the hallway on our hands and knees,” says Sockabasin, who recalls his earliest encounters with his new foster-father. “If the guy felt like it, he’d come give you a kick in the butt so hard that we’d fall and smash our face on the floor. Or he’d come upstairs while I was sleeping and slap the heck out of me with a belt.”

In his foster home, physical abuse wasn’t the only kind of violence that he suffered. His foster-father would frequently take him outside, away from the house, where Sockabasin says he was molested.

Terrified, angry, and desperate to escape, seven year-old Sockabasin ran away from home. He said he would have drowned in the Dennysville River if he hadn’t become ensnared in low branches on its banks. After he was finally found and taken back to the foster house, beatings by his foster father only intensified.

Sockabasin says his caseworkers were slow to do anything when he reported the abuse.

“I’d say, ‘I can’t live like this, they’re hurting me,’ and not one was doing a damn thing.

“I’d say, ‘I can’t live like this, they’re hurting me,’ and not one was doing a damn thing. They would wait about a year or two into it to do anything. Everything took ‘processes,’” he says. “Well, while ‘processes’ were happening, I would be getting my ass kicked.”

When Sockabasin’s caseworkers finally removed him from the Dennysville home, he was placed with a family in Bangor where he was again physically and verbally abused by the foster father. A year and a half later, after again reporting the abuse to his caseworkers, he was transferred to yet another home, in Corrina. Here, Sockabasin says, “All Hell broke loose.”

With his new foster-family, he equates his treatment to that of a servant, where he was made to do continual physical labor while the other children were well cared for. “These guys used to take all their kids out to the fairs, and have me stay back with a toothbrush and a water bucket to clean all the cracks around the house,” he recalls.

Still only eight years old at the time, Sockabasin again endured physical abuse at the hands of his new foster father. “Every now and again, he’d throw me on the ground, and take these thorns—thistles, I guess they call them—and he would rub them all over my chest until I bled,” he says. What’s more, Sockabasin witnessed the same man raping a foster girl in his care—Sockabasin says the girl was only 14 years old.

Finally, one Saturday while outside doing his chore of burning the family’s trash, Sockabasin decided he’d had enough. Matches in hand, he went to the barn and set it on fire.

“I didn’t care what was or who was in there,” he recalls. “After I did that, I walked down to the state trooper who lived down the road. I turned myself in because I wanted to be out of there. All I was trying to do was be with my mom and dad. To be home.”

While Aubrey Sockabasin’s childhood trauma may have started in the Maine foster care system, it didn’t end there. After turning himself in for setting the fire, Sockabasin spent 3 years in the Maine Youth Center, a correctional facility for minors, where he grew only more violent. He describes days in solitary confinement, sometimes locked to the toilet in his room, sometimes without a mattress to sleep on.

“All I was trying to do was be with my mom and dad. To be home.”

At the center, Sockabasin was ostracized by his peers and caretakers for being Passamaquoddy, and no serious efforts were made to encourage him to reconnect with his tribe or heritage. One year, as a joke, administrators presented him with a fake feathered headdress.

“I was turning into a rebel, I think, I was becoming something I’m not, that I wasn’t. But it was the only way I knew how to reach someone. I used to cut myself up—because all I wanted was to be back with my mom and dad.”

With yet another foster care home ruled out as an option for him, at age 11, Sockabasin was transported to the Bangor Mental Health Institute. “They had iron bars all over the place, people talking to themselves,” he says. “I knew what kind of place it was, I knew it was a ‘crazy’ place, and I knew I was going there.”

For years, he stayed in the institute, most of the time heavily sedated. Finally, one counsellor took an interest in Sockabasin’s rehabilitation and slowly weaned him off the drugs. Eventually, four years later, Sockabasin was released, but it would take years for him to come to terms with the trauma he had endured, and even longer for him to learn that his case was more common than he could have imagined.

Piscataqua River Bridge, which connects Portsmouth, NH to Kittery, ME (Flickr)

We Mainers are proud of where we are from. First, our beautiful state: Maine boasts a jagged coastline, and majestic mountains whose peaks offer vistas over New England to its south and Canada to its north and northeast. We’re also proud of our independent political streak, strong environmental protection laws, and our beloved outdoor sportswear companies.

The near erasure of our state’s original inhabitants goes largely unspoken of or simply ignored, if it is known at all.

The treatment of Native peoples, however, is a dark stain on Maine’s pristine image: the near erasure of our state’s original inhabitants goes largely unspoken of or simply ignored, if it is known at all.

Born into a white family in suburban South Portland, Maine, my own education about the state’s Native culture was nearly nonexistent. What little exposure I did have was limited to seeing tribal dances and drumming each year at the Maine state fair—as souvenirs, my sister and I would buy soft, leather-fringed pouches with colored beads sewn on the front.

The Big Indian in Freeport, ME (Robert Smith/Flickr)

Reminders of Native American presence in Maine were scattered around the southern coast where we lived. Tourists to “Vacationland”—Maine’s slogan in those days—would often pull over on the highway just outside of Portland to take pictures with “The Big Indian,” a 50-foot fiberglass figure that, since 1969, towered over whatever store it was supposed to promote: first the Casco Bay Trading Company, then a cheap chain clothing store, then a ski-shop. Rumor has it that during a recent restoration of the statue, workers had to remove the many arrows that had been shot into it, allegedly by college students.

“Native people are so invisible in this state,” Esther Attean tells me, not without some anger in her voice. Slender and energetic, with dark hair that falls below her shoulders, Attean is a Passamaquoddy tribal member, and one of the most vocal and recognized advocates for the TRC. We met last winter, when she attended an international conference at Columbia University on indigenous rights and truth commissions.

The youngest of seven children, Attean’s family is from the community of Sipayik, Pleasant Point, a reservation that sits at the easternmost point of Maine, at the basin of St. Croix River. Growing up, her parents and her older siblings spoke English as a second language.

A long-time activist for indigenous people’s rights, Attean’s years of work at the Penobscot Nation and the University of Southern Maine's Muskie School of Public Service allowed her to engage in an effort to help Maine's child welfare system, which was failing in its obligations to implement certain protections and provisions for Native children in foster care. She eventually came to be part of a group that germinated the idea for a truth commission.

“In Maine, we are challenging the dominant narrative that Native people can’t take care of their children, that the past is best left in the past, and that Natives and white people can’t work together.”

Today, she remains deeply involved with the TRC’s work as the Co-Director of Maine-Wabanaki REACH, a vibrant community network and cross-cultural collaborative comprised of staff from the State of Maine Office of Child and Family Services (OCFS) and Wabanaki child welfare programs, Wabanaki Health and Wellness, and the Wabanaki Program. REACH, whose name stands for “Reconciliation, Education, Advocacy, Change, and Healing,” founded the TRC, and continues to work closely with the commission to support its work, particularly in its direct engagement with Wabanaki and Maine communities. It is run by, and almost entirely comprised of, women.

At the indigenous rights conference in New York, Attean mingled with ease in the crowd of international scholars, researchers, and indigenous rights activists from places like Colombia, New Zealand, and Russia. As part of a panel discussion in an ornate room at Columbia University, she listened with quiet attentiveness to the other presentations. When it was her turn to address the group on the truth-seeking process in Maine, she introduced herself to the audience—first in Passamaquoddy and then in English.

“In Maine, we are challenging the dominant narrative that Native people can’t take care of their children, that the past is best left in the past, and that Natives and white people can’t work together,” she said.

Attean goes on to tell the history of Maine-tribal relations in a clear, matter-of-fact tone with a slight Maine accent. It’s a history she has had to explain many, many times before.

A Penobscot chief greets a Passamaquoddy chief and his aides at Maine's Fifth Annual Indian pageant held on the Penobscot Island reservation at Old Town, 1951 (AP Photo)

The French were the first Europeans to settle in Maine, in 1604; only later in 1677 did it become a part of the British colony of Massachusetts, and then gained independence as a US state in 1820. As European claims over resources, trade routes, and territory expanded, wars erupted and whole tribes were wiped off the map of what was to become New England.

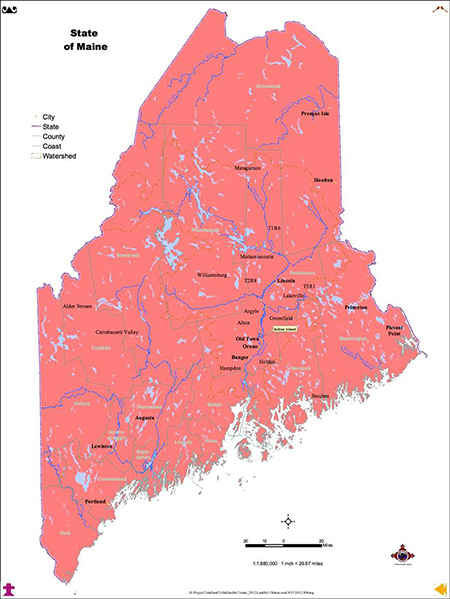

Map of Maine (Courtesy of Esther Attean)

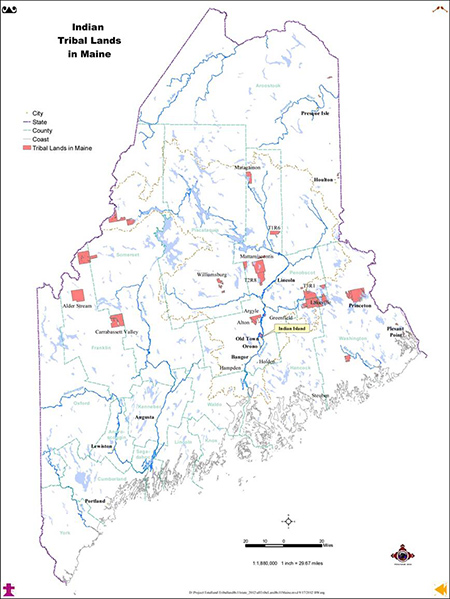

As Attean explains, Wabanaki people across the northeastern coast of the United States and Canada have suffered over a 95% population depletion since Europeans arrived. Today, only about 8,000 Wabanaki remain. The community centers of the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Micmac, and Maliseet in Maine are on reservations in the north and northeastern-most part of the state, several hours’ drive from Portland, the coastal southern city, and some are just a stone’s throw from Canada.

Negotiations between Native peoples and Europeans for land ownership—and sovereign rights to live on it—is a theme of contention that can be traced back from colonization of the Americas to the present day. In my own research, I was surprised to find that Maine has continually fallen behind the rest of the United States on reforms related to Native sovereignty, particularly in regards to its policies about land rights. In 1670, Sagamore Rowles, a leader for Native communities on the border of Maine and New Hampshire, complained of the injustice of buying back his land. On his deathbed, he offered a lucid prophecy of darker times to come:

Currently held indigenous land in Maine (Courtesy of Esther Attean)

Though these plantations are rightly my children’s, I am forced in this cage of evils, humbly to request a few hundred acres of land be marked for them and recorded, as a public act, in the “town book”: so that when I am gone, they may not be perishing beggars, in the pleasant places of their birth. For I know a great war will shortly break out between the white man and Indians, over the whole country. At first Indians will kill many and will prevail; but after the years they will be great sufferers and finally be rooted and utterly destroyed.

Legal battles between the tribes and the state of Maine over land ownership have continued since Rowles’ time, but under scrutiny today, however, is the harm caused to Native children and families as a result of Maine’s child welfare practices.

In her presentation, Attean points to the 1800s when the official US policy changed from violence and conquest of Native peoples to projects of cultural assimilation. Closely related to the network of missionaries that were converting Native people to the Christian faith, the effort to assimilate turned its focus on the linchpin of Native survival: the next generation. Richard Henry Pratt (1840-1924) was one of the most infamous proponents of re-education of Native children:

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.

Pratt established the Carlisle Residential School in Pennsylvania in 1897, which provided a model for dozens of other schools established to “re-educate” Native children or to assimilate them to non-Native culture. Wabanaki children from Maine and across New England were taken to the Carlisle School and other such schools. There, children were routinely abused physically, emotionally, and sexually. On a projector, Attean places faded photographs that exist from the Carlisle School showing hundreds of stoic-faced Native children, lined up in front of the school.

Esther Attean at Columbia University, NY (ICTJ)

Following in Pratt’s footsteps, the US federal government pressed on with its own projects to place Native children in non-Native homes across the United States, in order to observe how children could best assimilate to non-Native settings. In 1958, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the US Children’s Bureau funded the Indian Adoption Project (IAP), which was administered by the Child Welfare League of America. Despite the fact that “race-matching” was the dominant adoption practice of the time, the IAP placed 395 Native American children from 16 states into white families in the Eastern and Midwestern US. The Adoption Resource Exchange of North America (ARENA), the successor to the IAP, continued the practice, under another name. In 2001, the director of the Child Welfare League of America issued a formal apology for their role in the IAP and ARENA programs.

The reasons for higher removal rates of Native children vary, and many cases cite alcoholism or child neglect. However, as many studies have found, cultural misunderstandings about traditional ways of child-rearing in Native communities—especially the prominent role of the extended family—resulted in state agents mistaking these ways for signs of maltreatment.

Those who studied the effects of these adoptions observed that overwhelmingly, they caused children to be severed from their cultures and communities. Non-Native foster families were rarely given resources or incentives to offer native children connections to their tribes or extended families; language, community connections, and identities were lost. Many were placed in homes where they were physically and sexually abused.

In 1972, David Fanshel published a study of these adoptions. In his book Far From the Reservation, he observed:

It seems clear that the fate of most Indian children is tied to the struggle of Indian people in the United States for survival and social justice. Their ultimate salvation rests upon the success of that struggle. ... It is my belief that only the Indian people have the right to determine whether their children can be placed in white homes.

Amid growing advocacy by Native American and child welfare groups, in 1978 Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), which reversed the policy put in place by the IAP. The new law regarded children as “collective resources” that were essential to tribal survival and set up a number of barriers—such as tribal affiliation—for placing Native American children in non-native homes. The stated policy of the law is “to protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families.”

As with other issues related to Native peoples, however, Maine lagged behind the nation in implementing ICWA. Despite ICWA’s stipulations, Maine continued to have one of the highest rates of placement of Native children in non-Native homes. In 1984, this was 19 times higher than in other states, and in 1990, 16 percent of all Maliseet children were in non-natives homes.

The TRC Convening Group gathers at the signing of the TRC Declaration of Intent on May 24, 2011 (Seven Eagles Media)

In 1999 a federal government review found Maine to be officially out of compliance with ICWA. In an effort to reform state practices, the Maine Office of Child and Family Services invited the Wabanaki tribes to help the state to improve its compliance with ICWA. The ICWA working group, as it came to be known, delivered training for caseworkers, developed policy, and gathered baseline data about ICWA compliance.

But change wasn’t as simple as that, as Attean explained to the audience. Standing between their work and true reform of child welfare, she says, were unacknowledged feelings of mistrust, stemming from generations of displacement, oppression, white privilege, and racism.

“We trained over 500 workers in May of 2000 focused on the spirit and intent of the law, to show why it was necessary,” says Attean. “But we kept hitting what can only be described as an invisible wall. We realized we were trying to move on together without first talking about what happened.”

When the initial idea to establish a truth commission was suggested, it did not receive universal support. In fact, Attean says the prospect of having these stories come out in the public eye raised concerns.

“I remember one day just the anxiety and fear was so high. Somebody said, ‘We can’t do this, this is wrong, we can’t do this, because as soon as people start talking about this, people are going to start drinking and drugging and killing themselves,’” says Attean. “And then we stopped and said, ‘You know what? We’re already doing that. The silence is not working for us.’”

Because the proposed commission would look into the dark corners of Maine’s child welfare practices, the state of Maine also had its reservations. When I later spoke with Dan Despard, former State Child Welfare Director, he told me that when the idea arose to form a truth commission, he was advised not to attend the meetings. But Despard told his superiors that he felt an obligation to go.

“Somebody said, ‘We can’t do this, this is wrong, we can’t do this, because as soon as people start talking about this, people are going to start drinking and drugging and killing themselves.' And then we stopped and said, ‘You know what? We’re already doing that. The silence is not working for us.’”

“At first the instructions were ‘Ok, attend, but don’t commit to anything,’” said Despard. “But over time, the administration came on board.”

As various constituencies warmed to the idea, the ICWA working group—which included staff from tribal child welfare programs, the Department of Health and Human Services Office for Family and Child services, and the Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine—paved the way for the tribes and the state to sign the historic agreement to create a commission. Most of the group’s members were women.

On May 24, 2011, the chiefs and representatives of five Wabanaki communities joined Maine Governor Paul LePage to sign a Declaration of Intent for a truth commission in a ceremony on Indian Island. At the ceremony, LePage declared, “I am happy we are able to take this next step to continue this important effort. I see this Commission as a critical step to improve relations between the State and the Tribes.”

The Declaration of Intent is signed by the five Wabanaki Chiefs and Maine Governor on Indian Island. (Seven Eagles Media)

Brenda Commander was also at the ceremony. “As the Chief of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, a mother, and a grandmother, I know the incredible importance of our children,” she said. “The disproportionate taking of our children threatened the survival of our Tribe. I am pleased that the State of Maine stands ready to acknowledge the mistakes of the past and move forward on a new path guided by systems of reform and best practices for our children.”

A year later, a mandate for the commission was signed in Augusta, and the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission was born.

Traditional drumming at a Wabanaki Arts festival, Brunswick, ME, 2012 (Bowdoin College)

Since 1983, nearly 50 truth commissions have been enacted around the world after times of widespread violence or societal trauma. Today, countries as diverse as Tunisia, Cote d’Ivoire, and Nepal are all in various stages of establishing and operating national truth commissions on past violations of human rights.

A priest from the Guatemalan Mayan community prepares to perform a traditional ritual at the archaeological park of Kaminaljuyu (Hill of the Dead in Quiche) in Guatemala City. (Eitan Abramovish/AFP/Getty)

Increasingly, indigenous rights groups are considering ways in which measures like truth commissions can help to address historical and intergenerational trauma of past and ongoing abuses committed against them. One of these is the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which is dealing directly with issues that are in many ways related to those concerning the Maine TRC, namely, abuse against native children in Canada’s Indian Residential Schools. The Canada TRC came about as a result of a settlement in Canada’s Supreme Court between the government and First Nations. Since opening in May 2010, it has conducted research, gathered testimony, and engaged the public in an effort to shed light on the truth about Canada’s Indian Residential Schools. The magnitude of the legacy of the residential schools has been matched by robust public events across the nation, and thousands have given testimony in front of the national body.

What sets the Maine TRC apart from truth commissions like these, however, is that the TRC is not solely of the state of Maine or solely of the tribes—instead, it is a partnership between sovereign political entities meant to address historic rifts that have existed between them.

What sets the Maine TRC apart from truth commissions like these, however, is that the TRC is not solely of the state of Maine or solely of the tribes—instead, it is a partnership between sovereign political entities.

This type of innovative approach is highlighted in new research done by the International Center for Transitional Justice into ways that truth-seeking projects, like truth commissions, can be re-imagined to better address the experiences and rights of indigenous peoples. Instead of seeking to reaffirm the goals of unity and reconciliation within a nation-state, truth commissions can work to bring distinct nations together, going beyond a state-centric view of truth seeking and transitional justice. These commissions may also best engage with indigenous peoples when they’re designed to hear the stories and history not just of individual people, but the story of tribes and communities. In these ways and more, indigenous peoples are using new international tools to tell their truth. Truth commissions focused on the rights of indigenous peoples, and run by indigenous peoples, may not be just an effort to produce information about violations, but also an exercise in the right to self-government. Such commissions should be the result, as is the case with the Maine Wabanaki TRC, of careful consultation among indigenous peoples, always subject to the previous, well-informed and free consent of its participants.

On February 12, 2013, the day the Maine Wabanaki TRC was to formally “seat” its commissioners, a snow storm hit southern Maine, slowing to a crawl my 120-mile drive from Portland to Hermon. But the weather didn’t deter more than 100 people from arriving in the barn-style event hall to witness the ceremony. In the air, there was a tangible sense of gravity, but also of excitement. On the front page of the Portland Press Herald, even the weather-related headline seemed connected to the spirit of the day: “Time to Dig Deep.”

The five commissioners of the TRC are seated, February 12, 2013 (Hannah Dunphy/ICTJ)

At the ceremony, the audience—which included elders and infants, native and non-native—listened intently to speeches and dedications of the commission’s work, and witnessed the formal seating ceremony.

The commissioners of the TRC are both indigenous and non-indigenous and bring a variety of professional backgrounds to their roles. They are: Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap; gkisedtanamoogk of the Wampanoag tribe; Educator Carol Wishcamper; Dr. Gail Werrbach, director of the University of Maine School of Social Work; and Sandra White Hawk, member of the Lakota Sioux.

Seated next to each other on the small stage, the five commissioners sat with a sense of pride, solemnity, and determination, listening to statements from chiefs, tribal leaders, state officials, and drivers of the TRC process. Many of the speakers who were there in formal roles referred to traumatic incidents relating to adoption and the foster care system in their own personal lives or the lives of their family. Some people who spoke were non-Native siblings of someone who had been adopted into their own family. Though I was technically attending to report from the event, I felt more like a participant than an observer. After several hours of remarks, prayers, and a tobacco ceremony, the importance of the task ahead could be felt by all.

Representatives from Maine’s child welfare services also attended the ceremony. At a late-afternoon coffee break in the day’s activities, I had the chance to speak with Dan Despard, former State Child Welfare Director, and Virginia Marriner, former Director of Maine’s Child Welfare Policy and Practice. At this point, the snow had subsided and the sun had come out. As we stood in the front lobby of the event hall, small flocks of rambunctious children ran past us and out the front doors to the snowy parking lot, blasting us with frigid winter air.

“It’s a day of celebration for a lot of folks,” says Despard, who has to stoop a bit to speak into my recorder. “What is most important about this day for me is that my native friends who started this are seeing it come to fruition—Esther Attean and Denise Altvater—those are two really strong women who kept this moving, despite all the obstacles.”

The five commissioners of the TRC (Upstander Productions)

Both Despard and Marriner were members of the original convening groups that were formed to improve relations between Maine’s child welfare services and the Wabanaki. Marriner originally started her career as a caseworker at age 22 in the 1970s. She tells me she was assigned to many cases involving children from the Penobscot reservation and remembers wanting to work with the tribe, but not having formal processes to do so. She says the TRC process will help the state see where it made mistakes and how to improve.

“It’s the state seeing and recognizing the tribes as an equal entity—it’s not the state doing to [the tribes], but what we’re doing together.”

“It says a lot about the connectiveness in Maine, to see community as a whole entity,” said Marriner. “It’s the state seeing and recognizing the tribes as an equal entity—it’s not the state doing to [the tribes], but what we’re doing together.”

Despard emphasizes the value of learning the truth about past practices. “If you’re in the child welfare field, you need to understand the lessons of past abuses,” he said. “There are still Native children who are removed, and separated from all they know.”

Site of the seating ceremony for the TRC in Hermon, Maine (Hannah Dunphy/ICTJ)

As the TRC set out to begin its work, the immediate challenges were many: the commission had to find office space, raise money to support its activities, and hire competent staff to run its operations. Preparations for gathering statements were extensive, and volunteers were trained. Over the summer, the commissioners met with tribal leaders to seek guidance on things like the appropriate language to use when they entered Wabanaki communities.

TRC Commissioner Carol Wishcamper, left, and Esther Attean (Upstander Productions)

I spoke with TRC Commissioner Carol Wishcamper late this summer in downtown Portland, to hear about the progress of the commission. Wishcamper, who has short shock-white hair and red-rimmed eye-glasses, is the former Chair of the Maine State Department of Education. Sitting across the conference table from me, she answers my questions quickly.

“The people who come forward have horrific stories,” Wishcamper tells me, “full of trauma.”

The challenge, however, it seemed, was finding people who were willing to testify.

“At [the seating ceremony], it seemed like there was a real readiness for people to come forward,” she tells me. “It was only later that I realized that really only a fraction of people are ready to tell their stories.”

“It was only later that I realized that really only a fraction of people are ready to tell their stories.”

When the commissioners first travelled together in a delegation to Wabanaki communities to take testimony, the response was underwhelming. Even individuals who agreed to share their story would be overcome with hesitations, resistance, and fears about the implications of coming forward. In one mission to collect testimony, Native community members in northern Maine exhibited mistrust and expressed their unwillingness to give testimony to TRC volunteers who were non-Native, forcing the TRC to adjust their approach to collecting statements.

However, slowly, as communities learned more about the TRC—largely due to the work of community organizers from REACH—confidence in the process grew, and the numbers of survivors and families willing to share their stories started to increase.

The Commissioners of the TRC light a ceremonial fire at dawn at the onset of statement gathering in Wabanaki communities (Courtesy of the TRC)

So far, the TRC reports that it has received hundreds of testimonies, from Native and non-Native people alike. Wishcamper says that they’re hearing from people with a range of experiences, including many stories of Native parents who say, due to poverty and lack of opportunities on the reservation, they voluntarily placed their children in the foster care system, hoping they would have a better life. She says she has been moved to witness these testimonies.

“In several instances, people were relieved to be able to talk about it,” she says. “To be witnessed, to be affirmed, that it was real, that it happened to them, that there was a reason their lives have been as they are, and to have other people notice and care . . . The event could be 50 or 60 years ago, but the experience is still alive in them.”

A participant in the Maine Eastern Tribal Indian Society Pow Wow (Portland Press Herald)

“You know something,” Sockabasin says slowly, as if realizing something for the first time. “I’m angry at everything, but I don’t find fault.”

Decades later, Sockabasin is married and living back on the reservation at Indian Township, where he says he’s been accepted back by the community with open arms. Over the past 21 years, he’s worked for the reservation’s housing, health clinic, and public works. Sockasin even worked for child welfare as an investigator, working with Native children in the foster care system, a job that he took on with intense dedication.

“Everyone respects me here,” he says, when we speak on the phone this fall. “I’m way out in the boons. I don’t have a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out of, but I’m happy for me, for making it as far as I did. At least I get up in the morning, I put on my shoes, and I’m fine.”

“If I had been here, I would have been able to talk Native American to all these people, but I can’t. That complicates my life around here, because this is family.”

Today, what Sockabasin says he struggles most with is the Passamquoddy language, which is spoken widely throughout his community.

“If I had been here, I would have been able to talk Native American to all these people, but I can’t,” says Sockabasin. “That complicates my life around here, because this is family, and when they talk Indian, well, it’s like, ‘Sorry, that’s all I can say.’”

When I asked Sockabasin what his reaction was to learning that there would be a truth commission, he answers without a missing a beat: “Where were you guys when I was growing up?”

It was Attean, among other REACH organizers, who first asked him to give his testimony to the TRC. Sockabasin says he is not ashamed of telling his story and hopes it can be a way of helping others to know they are not alone.

“The TRC has helped me a great deal by dealing with [...] my problems, and what happened to me,” he says. “It’s like a group to me, everyone telling their side of the story. It’s basically all the same as what I went through.”

Community activities at Indian Township during a visit of the TRC Commissioners (Courtesy of the TRC)

Meanwhile, those who worked to establish the TRC are already thinking about what happens next. The leadership of REACH is talking about projects beyond truth seeking, to facilitate healing in Wabanaki communities, alternative economy projects, and ways to make sure Native traditions are passed on to the next generation.

What’s clear, however, is that everyone behind the TRC process is eager to hear what the final report will say. They stand committed to seeing that the TRC’s recommendations for reform and remedy are placed in the right hands and have the right political backing to set them in motion.

“Right now, we’re in the trees and it’s hard to see, but it’s nice to have that hope that what we’re doing here could reach other parts of the country,” says Wishcamper. “This is rooted in Maine, but it has national and international significance. It feels like even though our portion will end, it is just one step on a longer journey.”

As the TRC prepares to write it final report, anticipation is building about what the findings and recommendations will be. But due to pervasive dismissal and ignorance of “Native issues” in the state, it’s clear there is anxiety about how the report will be received, and whether its recommendations will receive the political attention needed for real change to happen.

Another TRC Commissioner I spoke with this summer, gkisedtanamook, says ignorance about Maine’s history with Native people has always been the default.

“It’s purposeful why people don’t know about Indian country,” he tells me when we spoke on the phone in August. He points out that the disjointed histories of the “discovery” of America still remain largely unresolved.

“In the beginning of the year, I start out the course with one question: What can you tell me about Native American culture?” he tells me. “And every year it’s the same: not one hand goes up.”

“One from the boat, one from the shore,” he says. “Two different narratives. Two different stories.”

A respected educator and activist, gkisedtanamook is a Wampanoag from the town of Mashpee, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod. I first met him at the seating ceremony for the Maine Wabanaki TRC, where he exuded a dignified calm throughout the day. His appearance is striking—he wears a short Mohawk, earrings, and intricate layered jewelry around his neck.

Since 2005, gkisedtanamook has taught as an adjunct professor with both the Native American Studies and Peace and Reconciliation Programs at the University of Maine in Orono.

“In the beginning of the year, I start out the course with one question: What can you tell me about Native American culture?” he tells me. “And every year it’s the same: not one hand goes up.”

I think of my own education in Maine, and have no choice but to agree. In elementary school, fourth grade was the year we learned about all things “Maine.” To remember the names of Maine’s 16 counties, we were made to memorize a song that, ironically enough, was set to the tune of “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” and whose lyrics read like a war between America’s founding fathers and the Native tribes:

There’re sixteen counties in our state/ Cumberland and Franklin

Piscataquis and Kennebec/ Oxford, Androscoggin

Waldo, Washington, and York/ Lincoln, Knox, and Hancock

Sagadahoc and Somerset/ Aroostook and Penobscot

Our class read about backwoods survival skills in Hatchet by Gary Paulsen, and in an effort to make us interested in the mysterious northern regions of the state, we created imitation tourist brochures for places like Mount Katahdin, in Baxter State Park. Nowhere was it mentioned in our lessons plans that the mountain has been a sacred place for Maine’s Wabanaki people for centuries or that the greatest survival tale to tell in our state was that of entire tribes still living only hours north of where we were.

Twenty years later, I’m now a settled New Yorker, but I often travel north in the late summers to retreat with family and friends. I relish the isolation offered by the woods, mountains, and lakes. The precious days deep in the forest never fail to give me a shift in perception of time passing—days slow down, and my mind quiets.

Something I look forward to when I travel to the lakes of Maine are the loons. Similar in shape and size to ducks, loons have feathers of intricate black and white markings. Their eyes are a striking blood-red.

When night falls, loons reign upon the lakes. Their mournful calls are long, unearthly, and haunting. One night a few summers back, the loons’ songs jolted me awake in bed. I walked down from the lake house to the edge of the water, with hopes of hearing them again. The moonlight lit up the surface of the lake like floodlights, making the water shine a brilliant silver white against the black outline of the trees on the far shore. Standing on the dock, I looked out to the middle of the water. Sure enough, the black heads of the loons emerged.

Belgrade Lake , ME (Hannah Dunphy)

In Wabanaki folklore, the loon plays the role of messenger and loyal friend of the hero Glooscap, a central figure of Wabanaki spiritual legends, who is a great transformer. In one version of the Wabanaki creation myth, as told by Maliseet artist Gina Brooks, Glooscap arrived on earth and created the animals. He shot four arrows into four different white Ash trees, creating the four tribes of the Wabanaki federation: Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Maliseet, and Mi'kmaq. Since Glooscap’s departure, his friend and faithful servant, the loon--named Aquim, or sometimes Kwimu—still calls for him. Legend has it that when the Wabanaki hear the cry of the loon, they say he is calling on Glooscap.

I think about the inhabitants of the land that is now called Maine who might have stood where I stood, held in a trance by the loons’ calls—Wabanaki, French, British, or their descendants. Perhaps when the loons’ haunted cries frightened children in the dead of night, Wabanaki mothers told the story of Glooscap and Kwimu to their children, to soothe them back to sleep. It’s a story that, perhaps, Wabanaki children removed from their families never had the chance to learn.

In a time when the conquest and near-eradication of America’s Native peoples is largely ignored, calling a place like Maine home without knowing its history is agreeing to let the past play out endlessly on loop, where the history of the most marginalized people is the first to be forgotten in the undertow of cultural erasure.

In a time when the conquest and near-eradication of America’s Native peoples is largely ignored, calling a place like Maine home without knowing its history is agreeing to let the past play out endlessly on loop.

The stories that are emerging from the TRC are not easy to hear. They will no doubt be met with denial and disgust, causing some to turn away from the truth. But the people who are sharing their stories deserve our respect, and the experiences they relate deserve our attention. Our state’s participation in the TRC should not be considered a mere gesture, because the welfare of children is not just a “tribal issue.” Our borders with the Wabanaki—the people of the dawn—exist more in our minds than they do in reality: our histories are interwoven, and our futures are, too.

These stories that are coming out of the dark may be as mournful and haunting as the loons’ calls, but they are also calls for great transformation, and for a desperately-needed reckoning with the dark legacy of colonization. If we choose to hear them, we could usher in the dawn of a new relationship between nations.

(Gina Brooks)

The author would like to extend sincere thanks to Aubrey Sockabasin, the staff and commissioners of Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and members of Maine-Wabanaki REACH for giving their time and cooperation for this article.

Header photo: Marsh in Washington County, ME (US Fish and Wildlife Service)