It has been over 10 years since final report of Timor-Leste’s Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation (CAVR), which detailed the systematic abuses suffered by the Timorese people under Indonesian rule.

Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced when Indonesia invaded what was then Portuguese Timor in 1975, and many suffered from sexual violence, torture, and other atrocities. Around 100,000 people out of a population of roughly 1 million died during the next 24 years. In the violence that followed the UN-sponsored referendum on independence in 1999, Indonesian security forces and their Timorese militia killed over 1,400 people.

The CAVR was established in 2002 to seek the truth about what occurred, recommend measures to prevent future abuses and respond to the needs of victims. The CAVR held eight national public hearings and 52 local hearings, collecting statements from 7,699 victims, witnesses, and perpetrators, in addition to providing urgent reparations to 712 victims, establishing a national archive and documentation center, and promoting reconciliation through a variety of measures.

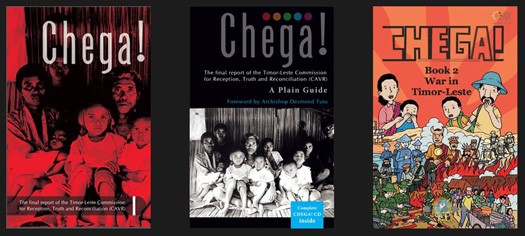

In 2005, the CAVR presented its final report, entitled Chega! – Portuguese for “no more, stop, enough.”

One decade later, what impact has the commission and its report had in Timor-Leste, and what lessons does it offer for the international community? ICTJ spoke with Patrick Walsh, an Australian human rights advocate who helped establish and advise the commission and served as senior adviser to the Post-CAVR Technical Secretariat.

The CAVR report was published over 10 years ago. Why is it still relevant today?

Chega! will not date because it addresses many of the big – sadly perennial – questions that continue to confront the world, including fundamental weaknesses in the international system and tolerance of impunity. The report does this in a highly credible, professional way, but is only now beginning to find its way into universities, key institutions, and think tanks in Indonesia and around the world. In addition, the crimes against humanity committed by Indonesia in Timor-Leste have not been addressed and will remain a stain on Indonesia and the world’s conscience until they are dealt with properly. Chega! is also a valuable case study and reference on human rights law, humanitarian law, and reconciliation processes.

How would you assess the impact of CAVR in Timor-Leste? What were its major successes?

Through its innovative community reconciliation program, CAVR made a critical contribution to grassroots peace in Timor-Leste following the trauma of 1999. At the time, Timor-Leste faced the prospect of serious blood-letting and payback that threatened the building of the new nation. CAVR also listened to a broad cross-section of stakeholders and developed an agreed common narrative about this tumultuous and decisive period in the country’s history. This has been documented in Chega! and preserved in archives, and a start has been made regarding its inclusion in the education system.

Chega! is also the first in-depth report to international standards on the behavior of the Indonesian military over a 25-year period. This was possible because the military withdrew in 1999 and witnesses were left free to testify without fear of recrimination. The report also holds up a mirror to the Timor-Leste resistance and offers many valuable lessons, both negative and positive, for the building of the new nation.

A report on the impact of Chega! in Timor-Leste will be available soon online. A recent report on its reception in Indonesia, entitled Inconvenient Truths, is available here.

Which recommendations of the CAVR report have been implemented and which haven’t? Why not?

Only a handful of CAVR recommendations have been formally acted on. These include the publication and dissemination of the Chega! report domestically and internationally, and a recent undertaking by the Timor-Leste government to consider the recommendation on establishing a CAVR follow-up institution. Others, such as human rights training for the security apparatus, have been implemented de facto in the normal course of public policy reforms.

Key recommendations on justice, reparations and archives have not yet been implemented. This is due principally to problems within the parliamentary system and the politics of Timor-Leste’s relationship with Indonesia.

What was the greatest challenge that the commission faced during its work, and what is the greatest challenge to implementing the report’s recommendations today?

The first question is addressed in some detail in Volume 1 of Chega! I think the biggest challenge was organizational – the challenge of building and operating a Timorese organization with an ambitious mandate from scratch in a country only recently recovering from the wholesale destruction inflicted by the departing Indonesian military and generations of neglectful colonialism.

The greatest challenge in implementation, perhaps unique to CAVR, is that some of the commission’s most important recommendations deal principally with human rights violations committed by Indonesia. Their implementation is therefore subject to the politics of the relationship between Dili and Jakarta.

The introduction to the report notes that the commission was not able to accomplish all it wanted in terms of truth seeking/truth telling. Why is this?

CAVR was certainly able to collect enough data, both domestically and internationally, to substantiate its troubling conclusions and findings on accountability. However, governments, including Indonesia, were generally not enthusiastic about the commission’s truth seeking about them and did not respond to CAVR’s requests to testify. It is to be hoped that the proposed CAVR follow-up institution will undertake further truth seeking/telling, in and outside Timor-Leste, and build on CAVR’s archival contribution to the nation’s somewhat threadbare written history.

The introduction also notes that more work remains to be done on justice, healing, reconciliation, and truth seeking. How can this be accomplished?

The recommendations on justice are a matter for the Timor-Leste and Indonesian justice systems and action by the latter, though long-term and a long shot, depends on continuing reformasi in Indonesia and a far better informed public. Due process on Indonesia’s part will also contribute to healing and genuine reconciliation. Indonesian and Timor-Leste civil society are already contributing creatively to healing, reconciliation, and truth-telling. It is hoped that donors will offer support and that the CAVR follow-up institution referred to above will enhance their work.

You mentioned the politics between Timor-Leste and Indonesia affecting the implementation of the CAVR’s recommendations. How exactly has the political and economic relationship between the two impacted implementation?

In addition to what has been said above, it is important to remind ourselves that Timor-Leste has land and sea borders with its large neighbor and, as it emerges from deep poverty and trauma and oil prices head south, now depends on Indonesia heavily for investment, educational opportunity, communications, and affordable goods and services. This economic relationship is being extended to military and other forms of cooperation. This leaves little if any wriggle room for justice and reparations for past crimes; both in fact are opposed by Timor-Leste’s leaders, even though a number of high-ranking Indonesian military officers have been indicted by the UN-supported serious crimes process. Timor-Leste’s policy is also a convenient fig-leaf for the international community, which also prioritizes good relations with Jakarta and has a vested interest in letting bygones be bygones.

Why hasn’t a reparations scheme, as recommended by the report, been implemented?

CAVR set out to be victim-friendly across all its work, so this recommendation – which focuses explicitly on the rights and needs of the many victims of torture, sexual violence, and other violations documented by the commission – was its most detailed, carefully argued, and important proposal. Timor-Leste has not officially said no to reparations; rather it prefers to ignore the recommendation and argue that its duty of care is being met through its social security, health, and other services.

Several significant factors have militated against its implementation. The principal official road block is the fear that it will open a Pandora’s Box of claims that will be difficult to verify, be extremely costly to meet and administer, and may well generate social jealousy and conflict. Difficulties administering an existing veterans program have added to this unwillingness.

For pragmatic reasons, Timor-Leste also prefers to ignore CAVR’s recommendation that Indonesia, governments which supported Indonesia militarily, and corporations which benefited from the war, should pay reparations.

Civil society continues to advocate acknowledgement, apologies, and reparations of one form or another for the most vulnerable victims. No legal action has been taken to challenge the constitutionality or legality of the government’s non-compliance, though the recommendation is arguably consistent with Timor-Leste’s constitution and international obligations.

You mention that Timor-Leste has ignored the several recommendations for the international community, including for countries that supported Indonesia’s invasion to help fund reparations for victims. What can the international community do to ensure that the report’s recommendations are implemented?

Countries named in Chega!, including the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, were effectively let off the hook in 2005 by then-president Xanana Gusmao, who distanced Timor-Leste from the report’s recommendations. The UN and its members have not debated or responded to the report or its recommendations. The recent publication of English and Portuguese versions of the report is an opportunity for follow-up on these matters.

Individual perpetrators may well have died before they are held to account, but, as the experience of many countries shows, it is possible that nations may admit responsibility and offer formal apologies and other responses in the future. Chega! and the CAVR archive will be critical to any such developments.

What are the needs of victims and affected-communities in Timor-Leste today?

Their suffering and contribution to the country’s liberation is not being acknowledged or honored to the same degree as the military component of Timor-Leste’s resistance. Women victims of rape and their children are vulnerable to discrimination. Children taken to Indonesia during the war remain separated. Timorese continue to grieve and search for the missing.

The justice deficit also galls. Timorese welcomed low-level perpetrators back into their communities, but no Indonesian military have been held accountable for the crimes against humanity and war crimes that CAVR, the UN serious crimes process, and other inquiries identified. The government, for its part, insists the focus should be on current development challenges. ACBIT, a Timor-Leste NGO, has recently completed a report on the situation of women victims today.

What lessons can be drawn from the CAVR experience?

A truth commission is not a quick fix. It is the first stage of a long process that requires sustained, long-term commitment and resources. CAVR and Timorese victims have additional, perhaps unique challenges, in that the major perpetrators were from a foreign country and, having returned there, are the beneficiaries of the vagaries and corruption of its justice system. Implementation of CAVR’s recommendations on justice and reparations in particular therefore depend significantly on the good will of Indonesia and the international community.

What is the legacy of CAVR in Timor-Leste today? In Indonesia? The world?

At the launch of Chega! in Jakarta in 2010, an Indonesian MP declared that it was a gift to Indonesia and to humanity. Based on a recent extensive lecture tour in Indonesia, I am confident that the current post-Suharto generation of lecturers and students value Chega! and are open to its contents and lessons. Chega! is also a compelling object lesson in the enormous human cost of impunity and the necessity for mainstreaming human rights and requiring compliance. It demonstrates that the world has a long way to go on that front and challenges us all, not just governments, to do far better. Archbishop Desmond Tutu is right that Chega! deserves to take its rightful place in the international canon of human rights and conflict resolution literature.